In this Exhibition

-

The Indestructible Object -

Self Portrait with a headband -

The Doll -

Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) -

The Two Fridas -

Birthday -

The Great Sirens -

The Eternally Obvious

Wall Labels

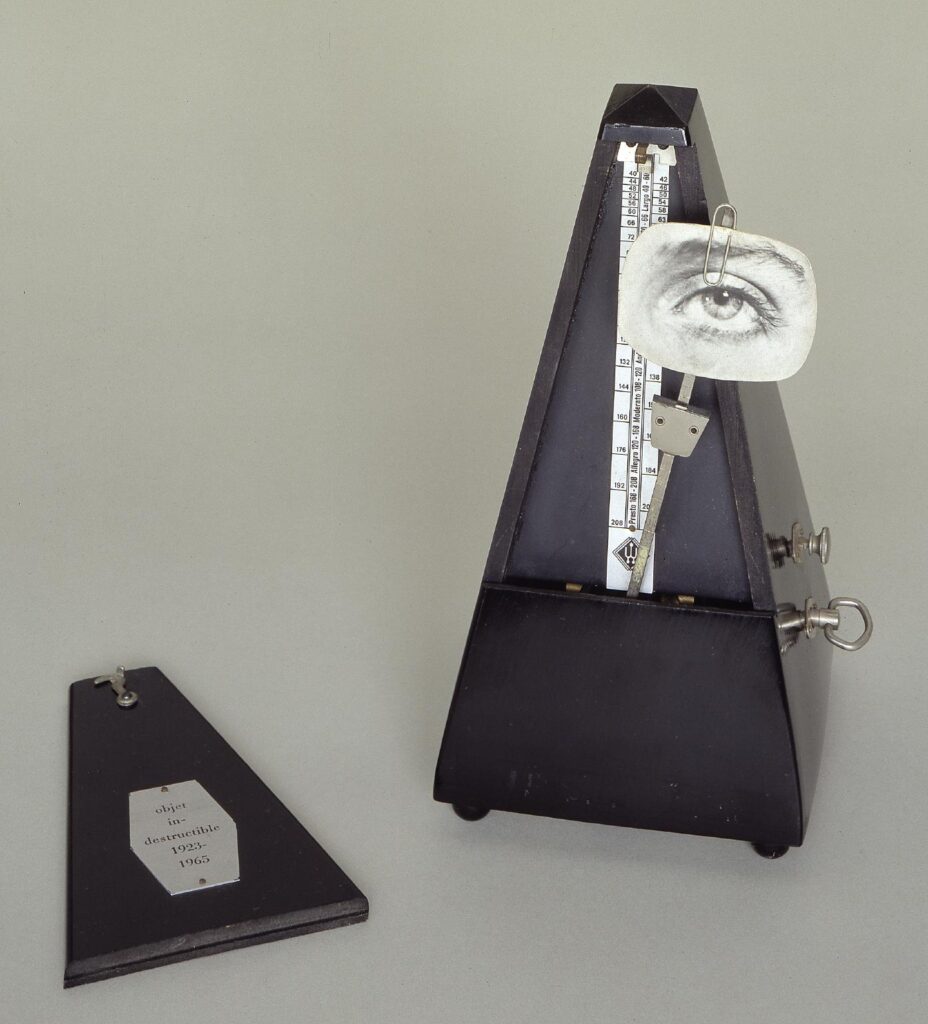

The Indestructible Object (1923-1965) by Man Ray

Date: 1923-1965

Artist: Man Ray

Title: Indestructible Object (or Object to Be Destroyed)

Source: Tate Modern

Media Credit: The Museum of Modern Art

Material: Meteronome

Dimensions: 8 7/8 x 4 3/8 x 4 5/8″ (22.5 x 11 x 11.6 cm)

Out of the other artworks in this exhibition, this piece has a unique history, as it was destroyed, lost and recreated over a period of 42 years (technically till 1982 as 2 posthumous examples were produced in that year). Originally, Man Ray used a metronome during his sessions of painting, with which he would match his rhythm with. If painting was not good, he would destroy the metronome, hence, the title, Object to be Destroyed. He later clipped a picture of an eye to the metronome, as according to him, a painter needed an audience. In 1932, Man Ray recreated this object for exhibition, and attached a picture of Lee Miller’s eye, his lover who had left him after 3 years. He even left instructions, urging viewers to attach the eyes of their lover and ultimately destroy the object. In 1940’s when Man Ray left Paris, the artwork was lost and later remade in New York. During 1958-1965 Man Ray made multiple copies of the artwork, one of which is depicted here, and it was named Indestructible Object (1923-1965).

It is seldom seen that an artist is willing to destroy a work of art. This is because this was the picture of one of Man Ray’s lover and with it brought him pain, and, although, it can be destroyed (an Object to be Destroyed) it would not leave his life no matter how many times he did destroy or lose it, hence, the title Indestructible Object; it was a constant reminder of what had been. It should, also, be noted that in this and many other Surrealist works, women are often objectified under a single idea, here the lover is represented only by her eye as that maybe all she surmounts to in this work of art.

Self Portrait with headband, New York Studio, USA (1932) by Lee Miller

Date: 1932

Artist: Lee Miller

Title: Self Portrait with headband, New York Studio, USA

Source: National Galleries Scotland

Media Credit: National Galleries Scotland

Material: Black and white photograph (vintage print)

Dimensions: 25.20 x 20.40 cm

Miller returned from Paris in 1932, and established her own photographic studio in New York. In this picture we see Miller’s profile herself as the model in a closely cropped shot of her profile. Lee used a half plate studio camera which could not focus at close range, so she had to shoot a full frame shot, and make an enlargement for the close-up. The cinematography is well done, with the curls of her hair matching the ruffled trimming of her gown and her pastel complexion in contrast with the velvety black dress. It is one of a series of photographs taken during the photo shoot which show Miller an upholstered armchair in several poses. This picture highlighted a plastic headband and this is of importance as the 1930s was well before plastic became a common item in the American household.

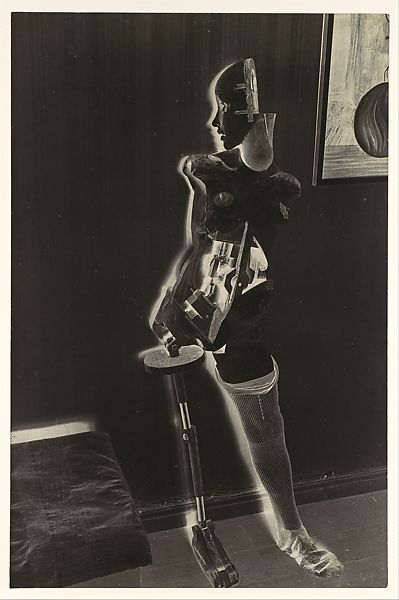

The Doll (1934–35) by Hans Bellmer

Date: 1934–35

Artist: Hans Bellmer

Title: The Doll

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Media Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Material: Photograph (Gelatin silver print)

Dimensions: 29.5 x 19.4 cm (11 5/8 x 7 5/8 in.)

The Doll is a hand-colored black-and-white photograph of a partially dismembered life-size doll. It is inspired by Jacques Offenbach’s (1819-1880) final opera The Tales of Hoffmann, where the hero falls in love with a realistic life-size mechanical doll. The artist took a number of photographs of The Doll in various poses and stages of construction and the photographs of the Doll became as important as the sculpture itself. The robotic female in this negative print creates mixed feelings within the viewer as it cannot be viewed as either human or as a machine. This picture, and his series of later pictures, represents the erotic, obsessive and self-destructive tendencies of the artist and mankind.

Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) (1937-1938) by Leonora Carrington

Date: 1937–38

Artist: Leonora Carrington

Title: Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse)

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Media Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Material: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 25 9/16 × 32 in. (65 × 81.3 cm)

Carrington was the daughter of a wealthy textile manufacturer and spent most of her childhood on a country estate where she interacted with animals and absorbed stories about fairy tales. Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) is one of her most recognized works and has been called her “first truly Surrealist work.”

Although, this painting may seem simple it is filled with symbolism. Firstly, horses were a central theme to Carrington’s paintings. In Celtic mythology, which Carrington was familiar with, Celtic goddess Epona often appeared as a white horse. The rocking horse above Carrington was possibly a reference to a young girl, in the play Pénélope written by Carrington, who loved her rocking horse Tartarus. The horse outside represented freedom and liberty whereas the hyena inside represented that same freedom and curiosity, but indoors. Carrington often identified with both the horse and hyena, something that becomes clear when we observe that her hair is drawn like a horse’s mane.

The Two Fridas (1939) by Frida Kahlo

Date: 1939

Artist: Frida Kahlo

Title: The Two Fridas

Source: fridakahlo.org

Media Credit: Museo de Arte moderno

Material: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 173.5 cm × 173 cm (68.3 in × 68 in)

Frida Kahlo is a Mexican artist remembered for her self-portraits, use of vibrant colors and her storytelling. Compared to other artists in this catalog, the paintings served as a backdrop to Frida’s tragic life. Frida suffered from polio from a young age and nearly died in a bus accident as a teenager. This led to multiple spine, rib and collarbone fractures, dislocated shoulder and a shattered pelvis. In her lifetime, she had over 30 operations. Emotionally, Frida, also, suffered from a rocky relationship with her artist husband Diego Rivera whom she married twice.

The Two Fridas was completed around the time of her divorce with Diego Rivera. This painting uses Surrealism to juxtapose two Fridas as well as organs i.e. exposed hearts. The painting on the left shows Frida in her formal Tehuana costume with a broken heart next to a Frida in a modern dress with a complete heart. The Frida on the right holds a small portrait of Diego while the Frida on the left holds a scissor which is used to cut the main artery of the heart. This painting represents the pain that Frida has to go through: one side on the left is the cold and formal side that detaches itself from Diego and feelings altogether while the right Frida still holds to her feelings but at the cost of clinging on to memories of her ex-husband. Still, both Fridas are connected by a vesicle meaning both are different parts of Frida. Frida is celebrated in Mexico and by feminists all across the world and is a small but important part of Surrealism which upholds diversity.

Birthday (1942) by Dorothea Tanning

Date: 1942

Artist: Dorothea Tanning

Title: Birthday

Source: Philadelphia Museum of Art

Media Credit: Philadelphia Museum of Art

Material: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 40 1/4 x 25 1/2 in

Dorothea Tanning is 32 years old in this portrait where she depicts herself standing naked in her New York apartment. The woman’s ruffled purple jacket adorns her naked chest with a skirt that has green tendrils growing from it. This green mass upon analysis reveals writhing human bodies, specifically reproductive organs. This picture represented Freudian themes of a dreamlike state as it is sexually charged and contains a series of infinite doors and represented Surrealist themes by juxtaposing a fantastical creature, which could be assumed to accompany her as she travels through these infinite doors.

This was painted right before Tanning interacted with her future husband Max Ernst who was scouting for works for gallery owner Peggy Guggenheim’s upcoming exhibition of 31 women artists. The reason why she titled her portrait Birthday has, also, been recorded:

“Please come in,” I smiled, trying to say it as if to just anyone. He hesitated, stamping his feet on the doormat. “Oh, don’t mind the wet,” I added. “There are no rugs here.” There wasn’t much furniture either, or anything to justify the six rooms, front to back. We moved to the studio, a livelier place in any case, and there on an easel was the portrait, not quite finished. He looked while I tried not to. At last, “What do you call it?” he asked. “I really haven’t a title.” “Then you can call it Birthday.” Just like that.

The Great Sirens (1947) by Paul Delvaux

Date: 1947

Artist: Paul Delvaux

Title: The Great Sirens

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Media Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Material: Oil on Masonite

Dimensions: 90 in. × 11 ft. (228.6 × 335.3 cm) The Great Sirens is one of Paul Delvaux’s largest paintings. The picture depicts a group of partially nude women in moonlight, sitting motionless before a hill bearing two Greco-Roman style buildings. Giorgio de Chirico is assumed to be an inspiration for this painting. The fair skin and flawless composition of the woman put them in contrast with the dark background of the painting. It is important to note that this painting features linear perspective and creates depth within the painting. Each siren is depicting smaller and smaller the “deeper” into the painting we look. Although, a woman being unconscious and naked would invoke feelings of vulnerability in this painting it invokes feelings of eroticism and menace. In the distance, a group of mermaids mesmerizes a lone man in a bowler hat. This painting portrays women in their seductive and threatening form

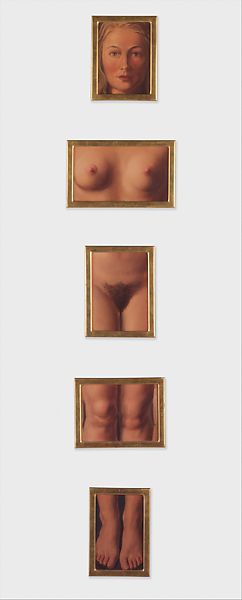

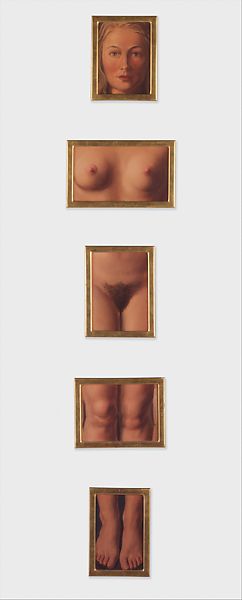

The Eternally Obvious (1948) by René Magritte

Date: 1948

Artist: René Magritte

Title: The Eternally Obvious

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Media Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Material: Oil on canvas mounted on board

Dimensions: Overall: 78 in. × 24 in. × 1 3/8 in. (198.1 × 61 × 3.5 cm)

In the painting Eternally Obvious Magritte isolates what he believes as “obvious” and leaves out the rest. The Eternally Obvious plays with the viewers perception as although we see individual body parts, we can construct the whole body from them. This work is a variation of a prototype made nearly twenty years earlier, which is now in the Menil Collection, Houston. Both were created in the same manner: Magritte first painted a nude portrait of his wife, which he then cut into 5 segments, framed, and (in some cases) reassembled onto a sheet of glass.